Li-Fi Standard Is Coming To Light Up Wi-Fi With A 100X Speed Boost

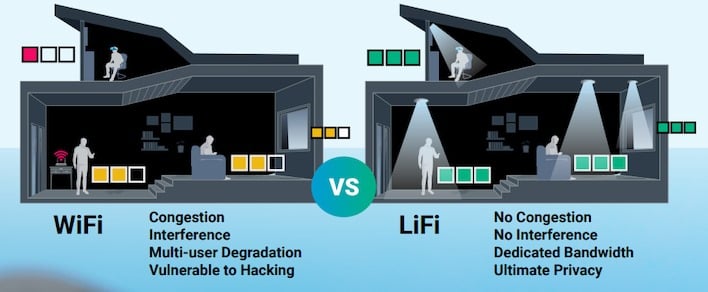

As technology enthusiasts, we all have a love-hate relationship with Wi-Fi. It's so convenient, the way it enables devices to access networks including the internet in a totally untethered fashion. It's also super frustrating at times, with unreliable connections and poor performance in crowded areas. Most of this is down to radio interference, as the frequency bands in which Wi-Fi operates are heavily congested.

Image: PureLiFi

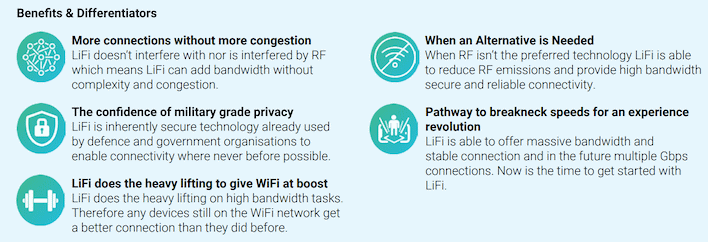

What if you could achieve a faster and more stable connection anywhere your device can see light? That's the promise of Li-Fi, a new standard that pulses regular old LED lights at rates and frequencies invisible to the human eye to enable high-speed data transfer. The group promoting the technology promises transfer rates as high as 224 GB/second using the new method, and says that it's not susceptible to interference like radio signals.

Of course, it is susceptible to forms of interference like, say, fabric, or walls—after all, when you're transmitting data using visible light, the light has to reach the receiver. The Li-Fi developers readily acknowledge this, and note that Li-Fi is able to be fully-integrated with existing Wi-Fi standards. In other words, it's not aiming to replace Wi-Fi, but rather be another standard that will live alongside the radio form.

Image: PureLiFi

Li-Fi has been in development for some time now, but the most important step toward the development of commercial products was just achieved: an IEEE standard. IEEE 802.11bb, specifically, addresses interoperability of Li-Fi and Wi-Fi. It was championed by the Light Communications Task Group, which was formed in 2018 to consolidate several emerging light-based networking technologies into a unified standard.

The list of companies planning to introduce Li-Fi technologies is pretty long, and includes names like Panasonic and GE alongside a litany of start-ups with names like Spectrum Networks, LiFi Labs, and PureLiFi. The latter company has been working on this stuff since 2012, and it just announced mass production for a product known as "Light Antenna ONE". It allows for 802.11bb compliance by appearing to an extant mass-market Wi-Fi chipset as if it were another band of Wi-Fi.

The video below from Fraunhofer HHI—one of the founding members of the Light Communications Task Group—explains how Li-Fi could even re-use a building's existing lighting infrastructure for data. It also notes that Li-Fi can be more secure than Wi-Fi owing to the fact that you need at least a reflected line-of-sight to one of the transmitters for it to work, meaning that someone's got to be peeking in your window to steal your data.

Given the publication of the IEEE 802.11bb standard, Li-Fi devices should become available to the general consumers within the next year. It will be interesting to see if the new tech gets widely adopted given its limitations.